Griffith Woods had been calling me since last year when I first read about the number and variety of huge trees located there. We delayed our hike due to deer hunting season and because winter would allow for better visualization and appreciation of the trees’ structures and details.

Griffith Woods Wildlife Management Area is a 746 acre facility located 4 miles southwest of Cynthiana, Kentucky. Beginning in approximately 1810, the land was continuously farmed for almost three centuries and is felt to be the best remnant of Bluegrass Savanna left in Kentucky.

The Bluegrass Savanna habitat was an open woodland characterized by the presence of huge, centuries old Blue Ashes, Bur Oaks, and Chinkapin Oaks, with grasses and forbs (non-grass flowering herbaceous plants) making up the understory. For millennia, the ecosystem balance was maintained by the presence of huge herds of buffalo and as well as other foragers like elk and deer. In contrast to other grasslands, fire did not play a significant role in the ecosystem. Native Americans used the area for hunting but reportedly did not have any permanent villages in this region.

When settlers entered Central Kentucky they found that these open woodlands with fertile soil were ideal for farming, with horses and cattle replacing the grazing roles of the buffalo and elk. Thus the foundation of the open woodland was maintained, although eventually agricultural grasses replaced the native grasses and forbs. The large trees were not significantly harvested as their contorting architecture with many low branches did not yield practical lumber and thus were left to provide shade for the livestock.

Griffith Woods does not have hiking trails, it has hiking avenues.

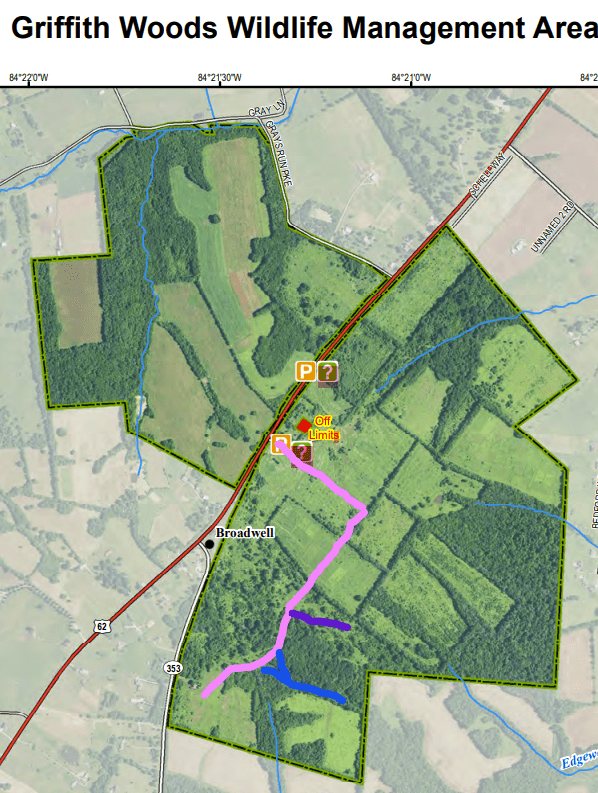

The staff mows wide swathes through the fields and, to be honest, they are numerous and can be confusing. These allow for vehicular travel for staff and disabled visitors. Smaller mowed trails venture off in what seems to be every direction.

There is no trail signage so I suggest that you ping you parking location on Google Maps so you can easily find your way back.

Once upon the hike, the first “oddities” noted were large clumps of bamboo. There appeared to be a couple different varieties and I do not know if these are of the 3 species native to Kentucky or ornamentals.

The old pastures that we walked through have various durations of idleness, so the fields are undergoing plant succession at different stages, with pioneer trees replacing the field plants and grasses. That is one of the challenges facing the managers of Griffith Woods; how do they maintain the open woodland and grassland without grazers being present?

I have read that another concern about the future of Griffith Woods is whether the iconic oaks and ashes are reproducing, and there has been some planting of these native trees to ensure replacement. Certainly the most abundant young trees growing in the fields were Walnuts, but I did see some Hickories, Blue Ashes and this young Bur Oak, identified by the classic finding of buds clustered at the end of the branch, as noted in the photo, and Bur Oak leaves at its base.

No matter where you are in the world, an oak can be identified by its “clustered terminal buds”.

As we continued to meander down the avenues we came upon our first of many multi-century old trees. This one appears to be of the white oak family (Bur Oak or Chinkapin Oak).

And while the Oaks and Blue Ashes are the trademark species of the Bluegrass Savanna, Griffith Woods also features huge Shagbark and Shellbark Hickories.

With a telephoto lens we can see two interesting findings one hundred feet above the ground: The swelling of the Hickory leaf buds indicative of the upcoming spring, as well as the retention of the petioles (stems) of last year’s compound leaves. This is a finding that I saw more here than elsewhere on other hikes, and suspect that there may be a genetic basis for this.

At Griffith Woods, and the Bluegrass region as a whole, the Shellbark Hickory is referred to as Kingnut Hickory, because it produces the largest of all the hickory nuts. These nuts have thick husks and a flavor very similar to the taste of a Pecan, which is also a member of the Hickory family (genus Carya). There are however, hickories that do not taste so good: The appropriately named Bitternut Hickory for example.

The most common of the large trees at Griffith Woods is the Blue Ash. Luckily they are largely resistant to Emerald Ash Borer and experts feel that only Blue Ashes that are otherwise stressed succumb to the borer. Here we came upon an outstanding specimen.

It has this beautifully textured and woven bark.

Previously I mentioned the contorted architecture of some of these trees and that is particularly seen in the Bur and Chinkapin Oaks. For size reference please note me at the base of the tree in the first photo.

If you look closely at the photo below, what appears to be one tree is actually two, and of two different species: A Bur Oak married with a Shagbark Hickory.

As we ventured further west mistletoe became somewhat commonplace. In a previous article on mistletoe (https://footpathsblog.com/2021/12/17/mistletoe-for-me-its-a-southern-thing/), I commented that you do not often see mistletoe growing near the ground because it is a favorite browse of deer. But here we found it at eye level, growing on an armed honeylocust tree, and despite significant threat of injury, it was indeed being browsed upon.

Over this stretch of the terrain we saw some mature trees with particularly heavy mistletoe infestations, almost always in Walnut trees, that reminded the photographer of Dr. Seuss trees.

Recalling my Mistletoe article, she pointed out that I failed to mention that it is dioecious; meaning that it has male and female plants, and therefore you will see plants with and without berries, like hollies. Frankly, I was pleased that she remembered the details of the essay. With the abundance of Mistletoe here, the haves and have-nots was obvious.

The primary risk to being the tallest structure on a terrain is that you experience the brunt of the weather, both wind and lightning. Storm damage could be seen as we worked our way through the woodland. The first photo below shows where wind snapped off the crown of a Blue Ash, and the second shows damage from a lightning strike where the bark was blown off the trunk to the right. We saw several other examples as well. Luckily the trees can live for decades following one of these injuries. In fact, in the first photo you can see where a substantial new branch appears to be arising off the callus edge that is trying to heal the wound.

As mentioned earlier, Griffith Woods was a successful cattle and horse farm for centuries and there was evidence of that on this hike, including a water trough positioned to service two pastures, a derelict silo, and a massive collapsed barn that featured timber frame construction.

Two of the more exciting findings on this February 10th hike were some harbingers of spring, including the swelling and partial opening of the fuzzy hickory tree buds, and seeing this Blanchard’s Cricket Frog in a small creek. See the link at the end of the article for more information on this frog and to hear its call which will allow you to understand where it got its name.

“Soft” mast, or non-nut wildlife food sources, were abundant at Griffith Woods (rose hips, wild grape, and mistletoe berries).

At this point we started to head back to the parking area with a couple of small diversions as noted on this map.

Doing so under this peaceful mid-afternoon moon.

The only disappointment on this hike is that we did not find the National Champion Chinkapin Oak that is on site, nor the “Three Sisters” Chinkapins that is a photo waiting to happen. We will return in pursuit of these trees and to hike the areas that we did not visit today. The thrill and mystery of the hunt will bring us back.

In summary, Griffith Woods is an outstanding preserve that should be on every outdoor enthusiast’s list of places to visit. It is a unique ecosystem that demonstrates what the Bluegrass region was largely like prior to the arrival of European settlers. The stars of the show are the enormous trees that are amazingly commonplace on the campus. To be honest, the photos, as inspiring as they are, do not really capture the majesty of these trees. I do think that a visit on a pretty winter or very early spring day allows for the best appreciation of the iconic trees themselves. That said, late summer and fall hikes would offer field wildflowers and leaf color. The Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife is working to re-establish native grasses and field plants.

Photo credits to Peggy Juengling Burns.

Overview:

Location – 77 miles south of Cincinnati and 15 miles off the Georgetown, KY exit.

Parking – Large well maintained gravel lot for approximately 10 cars.

Facilities – None.

Trail Conditions – Easy. The trails are grassed. They were moist when we visited and the soil was spongy near the creek crossings.

Print Map Link – https://fw.ky.gov/More/Documents/GriffithWoodsWMA_ALL.pdf

Benches – None.

Kids – Kids 5 and over should do well here with minimal assistance.

Dogs –Welcomed while on a leash.

Paired Hikes – On this large facility there are numerous directions and unnamed trails one could take.

Links:

https://app.fw.ky.gov/public_lands_search/detail.aspx?Kdfwr_id=9201

https://eec.ky.gov/Nature-Preserves/Locations/Pages/Griffith-Woods.aspx

For narrated information on the Blanchard’s Cricket Frog see this link:

https://fw.ky.gov/Wildlife/Sound%20Files/Blanchard%27sCricketFrogNarration.mp3

For a more comprehensive understanding on the history, nature, and proposed management of Griffith Woods please see this link:

https://bluegrasswoodland.com/uploads/Griffith_Woods_Unrealized_Potential.pdf

Very nice blog and a wonderful looking property. We will visit it on a warmer day. Thank you!

It was 52 and sunny the day we went and it was very comfortable. We should get more of those days before things leaf out which would obstruct the views of the trees.

Pat, I have to ask! Near my home is a tree with those thorns! They bother me! Would like to have them taken down by the city but what is such trees use? You mentioned mistletoe. Really? Just wondering! Thanks for all your posts!

These trees are actually a significant food source for wildlife, especially the seed pods. The inside lining of the pods is sweet and that is where the term “honeylocust” comes from. The flowers are generally not an important source for honey production. Fruits are eaten by rabbits, gray squirrels, fox squirrels, white-tailed deer, bobwhite, starlings, crows, and opossum, and in the past, native Americans. The large thorns are thought to be a relic from the Pleistocene era when these thorns helped protect the tree from the mega grazers like woolly mammoth and giant deer.

And also, there are thornless varieties available in plant nurseries. They are felt to be good street and lawn trees because they are rapidly growing, their roots do not displace sidewalks, they have good fall color (yellow), and their leaves/leaflets are small and generally do not require raking in the fall.